Four-volumes of short, colorful introductions to every aspect of the world’s oceans.

Focused on marine animals, with beautiful watercolor illustrations

Entries for marine organisms, oceanographic phenomena, as well as biographical entries for navigators, marine scientists, whalers, and naval officers. Filled with lovely illustrations.

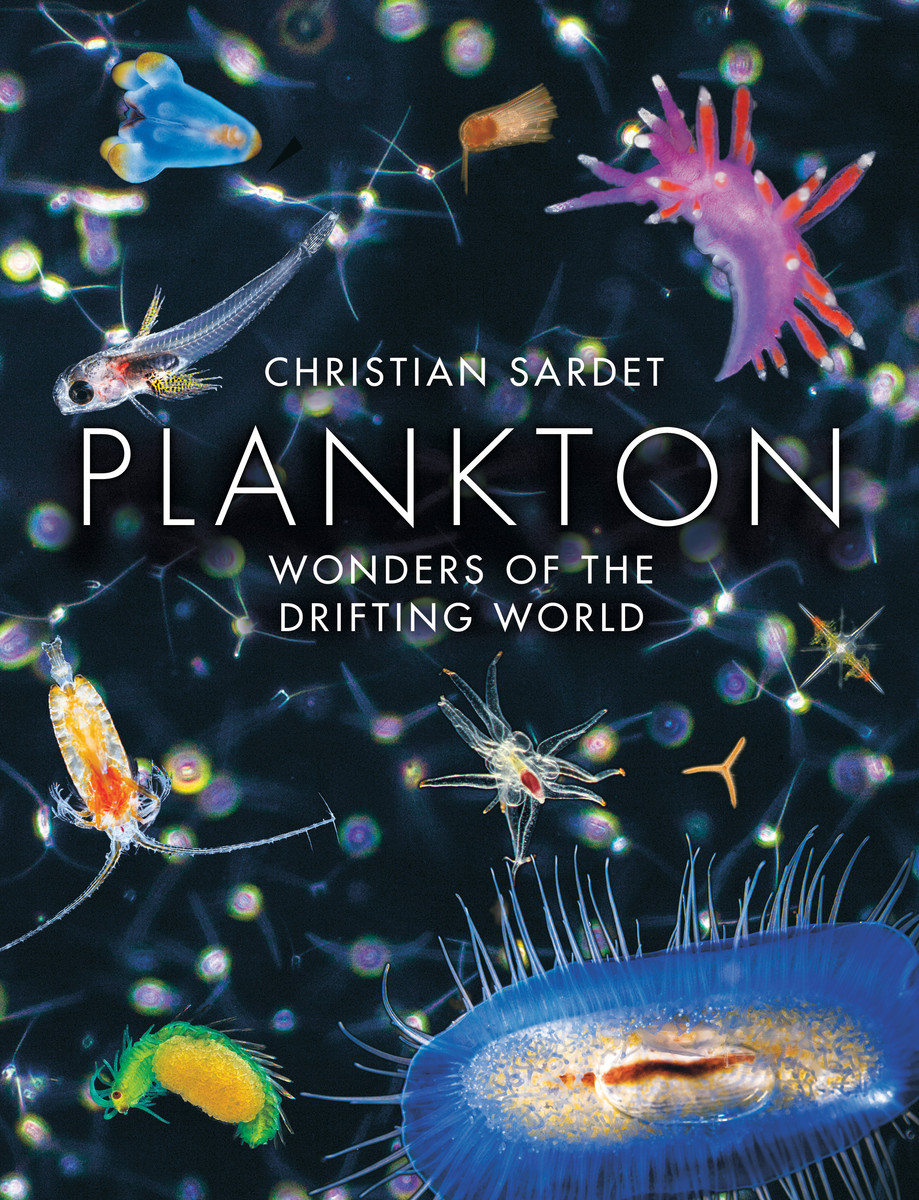

This is a beautiful book of photography of plankton through the microscope; it might just inspire you to do a plankton project, and if it does, it will be a great help as you learn to identify them.

In this version of a mind map, you put the thing that interests you at the top of the page or white board. This could be any aspect of the project that is meaningful to you. For example, maybe you want to do something involving field work in Penobscot Bay, but you’re not sure what; or perhaps you really want to use Littorina littorea in an experiment, but you’re not sure what hypothesis to test. Whatever it is that compels you, put it at the top of the page, and then start to map its various aspects:

You keep subdividing and drawing connections between items until something emerges as a possible research topic. The purpose is not necessarily to map out every aspect of a topic, but to map until something strikes you as interesting. In the following example, someone stopped as soon as they had the idea to measure water chemistry and compare it to rates of rainfall:

In this version of a mind map, you begin with an already-chosen topic and work “up” to consider the full range of more abstract scholarly conversations of which your topic might make a contribution.

You put your central empirical research question at the bottom of the page or workspace, broken down into its various elements, then think about the larger conversations that those elements are relevant to. A project that is asking a research question about salt marsh restoration, for example, could potentially contribute to conversations about salt marsh biology (that aren’t necessarily interested in restoration) and to conversations about habitat restoration (that aren’t necessarily interested in salt marshes in particular). Being able to think through all the possible conversations can allow you to more strategically situate your project in the literature. The example below shows how someone working on an experiment involving mussel shell strength could identify the full scope of relevant literatures.